Regulating Anxiety & Confidence Levels

Given the money at stake and the size of the audience, footballers at the elite level can be forgiven for occasionally choking under pressure. Further down the leagues, players know that failing to perform might spell the end of their professional careers. Youngsters in academies are also at risk of buckling under the weight of expectation. Many of them are seen as future stars by their families, but their chances of ‘making it’ are still minute. Former FA Head of Talent Identification, Richard Allen, stated that “only 0.5% of those signed by a professional club aged Under 9 will go all the way through to play in the club’s first-team”.

The fear of failure among footballers, from the Champions League right down to development teams, is understandable. When nerves take over, however, failure becomes far more likely and so it is important that coaches understand how to help players manage their anxiety.

Quite often, players will have no problem performing at their best in training, but struggle to reach those levels on matchday. In his book, Soccology, Kevin George refers to these individuals as ‘training ground internationals’. As we will discover, mental preparation in a variety of forms can help to bridge the gap between practice and competitive fixtures.

Understanding the problem

Before exploring the science behind performance anxiety and some of the key theories, it is important that we define the relevant terminology. Weinberg and Gould (2015) referred to activation as ‘cognitive and physical activity geared towards the preparation of a planned response to an anticipated situation’, while they defined arousal as a ‘blend of psychological and physiological activation of varied intensity’. Finally, anxiety is a ‘negative emotional state with feelings of worry and apprehension associated with activation and arousal of the body’.

Activation and arousal occur when the amygdala, the part of the brain associated with fear, responds to a perceived threat by releasing noradrenaline and cortisol into the bloodstream. These stress hormones increase heart rate, elevate blood pressure, and boost energy supplies, preparing our bodies to fight or flight.

This response is there to aid us in dealing with situations that are deemed important or threatening and without it, we would not be able to recognise danger and react accordingly. Some level of arousal is necessary for athletes to compete at a high level, increasing their focus, speed of thought and anticipation. However, excessive levels can hinder performance substantially.

When an individual is suffering from a heightened state of anxiety, their brain will often enter survival mode. Thoughts become restricted mostly to the primitive limbic system, preventing the higher-level thinking that occurs in the frontal lobes. In moments where problem-solving and creativity are required, this can lead to impaired performance.

Conversely, high levels of anxiety can also lead an athlete to ‘overthink’ in moments that call for a more automatic response. Part of our pre-frontal cortex becomes activated when we are learning a new movement, but when we have carried out a specific task repeatedly over a long period of time, the control of these movements becomes the responsibility of our cortex-basal ganglia-thalamus loop.

This transfer from our conscious minds to our unconscious minds allows us to execute certain skills efficiently and quickly without having to apply significant amounts of attention. Athletes often choke when they make the mistake of bringing conscious awareness to movements, as this disrupts the automatic processes that have been built up over years of practice.

It is important to note that the optimal level of arousal varies from one sport to the next. Rugby, for example, is a sport that requires primarily gross motor skills and as result, can generally cope with higher levels of arousal. However, Golf involves the use of fine motor skills and so maintaining relatively low levels of arousal is typically an essential feature of successful performance. Football, meanwhile, requires a somewhat even mixture of gross and fine motor skills. Therefore, it is logical to think that an optimum level of arousal for footballers lies somewhere between that of golfers and rugby players. Landers & Boutcher (1986) adapted Yerkes and Dodson’s Inverted U Hypothesis to account for different sporting contexts, as shown below.

While acknowledging the importance of arousal intensity, Jones, Hanton and Swain (1994) felt that how an individual interpreted symptoms was also crucial in determining how much performance anxiety they would experience. This was referred to as the ‘directional hypothesis’. Some athletes, such as Andy Murray, view symptoms as facilitative. Murray say’s “Being nervous is good. Having that adrenaline gets your mind focused”. On the flip side, other athletes might interpret symptoms in a debilitative manner. Former Barcelona footballer, Bojan, told The Guardian that earlier in his career, anxiety prevented him from performing at his best.

A number of factors can influence an individual’s response to physiological symptoms. Jones and Swain (1992) found that athletes with ‘competitive personalities’ were more likely to have a facilitative outlook. Hanton et al (2000), meanwhile, discovered that while rugby players generally viewed symptoms as facilitative, rifle shooters had debilitative interpretations. Finally, Perry & Williams (1998) found that both advanced and novice tennis players had facilitative outlooks, while intermediate players had a debilitative interpretation. These findings suggest that individual personality traits, the type of sport being played, and the level of competition can all play a role in predicting whether athletes will view symptoms as facilitative or debilitative.

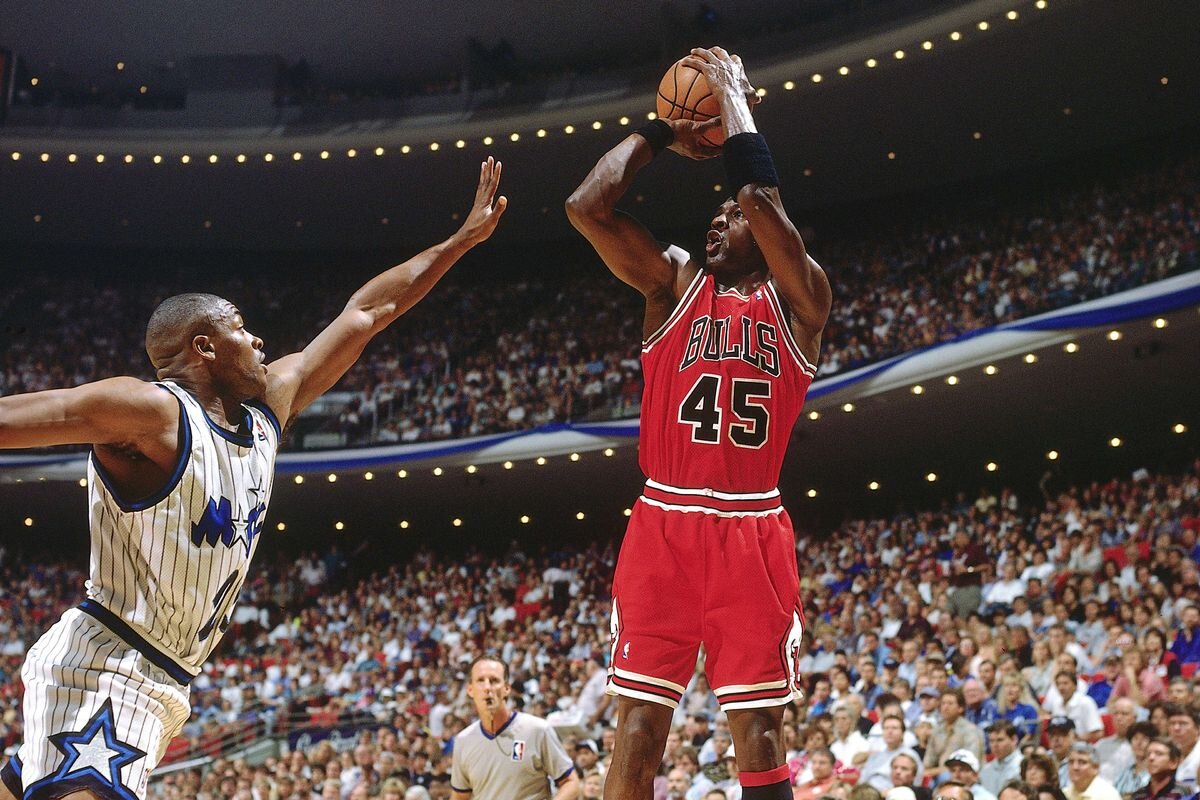

There have been a large number of studies conducted to test the directional hypothesis. For example, Chamberlain & Hale (2007) found that athlete’s interpretation of arousal was a more effective predictor of high performance than the intensity of arousal (42.5% vs 22.9%). With this in mind, it is clear that helping players to view symptoms in a positive light is essential if they are to perform under pressure. Former NBA star, Michael Jordan, seemed to thrive in high pressure situations. On players with negative outlooks, Jordan say’s “Those guys, when it gets stripped down, don't believe in themselves. They aren't sure they can hit the big shot, so they can't. It's a self-fulfilling prophecy”. As we have learned from the directional hypothesis, whether an athlete believes that symptoms of arousal will have a facilitative or debilitative impact on their performance, they are probably correct.

Ultimately, football is a mixture of solving problems and executing actions quickly. Excessive levels of arousal and a negative outlook of symptoms can decrease a player’s ability to function at their best. England manager, Gareth Southgate, speaks regularly about the importance of helping players to prepare their minds for competition. (source: Boot Room)

“There are lots of barriers for players which inhibit their performance – most of them psychological – so you have to try and make them overcome that and try and limit the interference in their performance.”

In order to achieve this, coaches should have an understanding of how the brain operates in high pressured settings, as well as having knowledge of the range of strategies that players can use to prevent anxiety from disrupting their performance. The rest of this article will focus on the latter.

Imagery

The first strategy we will look at, imagery, is defined by Vealey and Walter (1993) as “using all the senses to recreate or create an experience in the mind”. According to functional equivalence theory, imagery helps individuals to prepare for situations by “accessing, strengthening and refining the same neural pathways as when physically performing” (Murphy et al, 2008). In essence, imagery takes advantage of our brain’s limited capacity to differentiate between the real and the imagined. If practiced correctly, imagery can desensitise athletes to high pressure situations. Below, MMA trainer John Kavanagh explains how Conor McGregor uses the strategy to prepare for fights.

“He (McGregor) knew exactly what was going to happen long before it happened because he had done it a thousand times in his head. He had warmed up backstage, heard the crowd, smelt the arena, seen the audience.

By the time fight night came along, where a lot of people would walk out to 15,000 people and get shocked, he used to walk out going ‘yeah, this is my thousandth time doing this’.”

Munroe et al (2000) described two basic reasons that an athlete might use imagery. ‘Cognitive’ reasons include learning a new skill or improving the execution of a skill, memorising movement sequences, and planning or strategizing. ‘Motivational’ reasons include enhancing motivation levels, changing thoughts or emotions, or regulating physiological responses.

In order to ensure that imagery is realistic and therefore effective, it is advised that players use the ‘PETTLEP’ model when designing an imagery script (Holmes & Collins, 2001). Smith et al (2007) found that athletes who used the PETTLEP approach for 6 weeks performed better than those who used more traditional imagery (primarily visual imagery). The model is broken down below with football specific examples where necessary.

Physical- have a ball at your feet and wear relevant clothing/footwear.

Environment- recreate the competitive environment by practicing imagery while viewing images or video footage of the relevant stadium/pitch.

Task- ensure that imagery mimics the technical elements of the relevant tasks as closely as possible.

Timing- carry out the appropriate movements at relevant speed & try to maintain natural rhythm of movement.

Learning- adjust imagery to ensure that you are only imaging skills that you have successfully learned, as opposed to skills that you are unlikely to execute in reality.

Emotion- recreate the emotions that arise in relevant situation but replace negative thoughts with positive ones.

Perspective- practice either external imagery (watching yourself carry out task) or internal (point of view). Internal may be more suitable for ‘open-skill’ sports, such as football, where player must constantly react to surroundings.

Many top-level players use a more simplistic, primarily visual approach to mental rehearsal. In 2012, Wayne Rooney told ESPN “I ask the kit man what colour we’re wearing, if it’s red top, white shorts, white socks or black socks. Then I lie in bed the night before the game and visualize myself scoring goals or doing well. You’re trying to put yourself in that moment and trying to prepare yourself, to have a ‘memory’ before the game. I don’t know if you’d call it visualizing or dreaming but I’ve always done it, my whole life.”

Research that validates the use of imagery includes a study by Munroe-Chandler, Hall & Fishburne (2008), which found that among recreational & competitive youth soccer players, imagery led to enhanced levels of self-confidence & self-efficacy relating to their soccer skills. Vadoa, Hall & Moritz (2008), meanwhile, examined the relationship between imagery use, imagery ability, competitive anxiety & performance among Roller Skaters. Results showed that imagery can have a positive effect on performance by helping to control competitive anxiety levels & improve self-confidence.

Overall, it is clear that imagery can help athletes to reduce anxiety and perform at their best.

Self-Talk

Tod (2014) defined self-talk as “statements, said out loud or quietly, addressed to the self for a specific purpose”. Self-talk can be positive or negative. Carr (2006) stated that while negative self-talk can cause anxiety levels that challenge breathing and concentration, positive self-talk can enhance performance by relaxing the athlete. Former England and Manchester City goalkeeper, Joe Hart, has used self-talk throughout his career to help him boost confidence and reduce anxiety. Speaking via his YouTube channel, Hart say’s “Let any negative thoughts go and replace them with a positive, ‘I can’ or ‘I will’ statements. My routine fills me with the belief that I will play at my best.”

According to Tod et al (2011), there are four reasons for engaging in positive self-talk. Namely, to concentrate on relevant cues, enhance motivation levels, manage emotions, or produce efficient movement patterns. Self-talk can be either instructional or motivational. Instructional self-talk occurs when athletes guide themselves through specific elements of a task. For example, ‘strike the ball with the inside of your foot’. Motivational self-talk, meanwhile, involves either using relaxing messages to help ease anxiety, or inspiring messages to psych yourself up. It is important to note that for expert players, instructional self-talk can cause paralysis by analysis by disrupting automatic processes that have been developed through years of practice (Masters, 1992). Given footballer’s reliance on ‘ball mastery’, as well as the necessity to act quickly and efficiently, it is wise for experienced footballers to avoid instructional self-talk and focus on using motivational self-talk to regulate emotions.

A number of guidelines exist for the use of self-talk. Landin suggested that phrases should be as short as possible, cues should be task-specific and meaningful to the athlete, and the nature of the task as well as the athlete’s skill level should be considered. Kross et al (2014), meanwhile, proposed that athletes should refer to themselves as ‘you’ instead of ‘I’. For example, instead of saying ‘I wasn’t focused enough on that pass’, say ‘That wasn’t bad, but you need to be more focused on the next pass’. The belief is that this will result in less self-defeating messages and more objective, constructive feedback. Finally, Hatzigeorgiadis advised that individuals should always make sure that they use positive phrasing. For example, instead of saying ‘don’t panic’, say ‘stay calm’.

To demonstrate the effects of self-talk, Georgakaki & Karakasidou (2017) had one group of swimmers take part in a motivational self-talk training program, while a control group received no training. They found that self-talk training led to a reduction in competitive anxiety. Theodorakis et al (2001) tested the effects of instructional & motivational self-talk on basketball shooting performance. Only participants who used the cue ‘relax’ were successful in improving performance.

Provided athletes follow the guidelines above and use the appropriate form of self-talk, research suggests that it be an effective tool for relaxation and confidence enhancement.

Anything Else?

Setting simple tasks can also help to relax a player’s mind during competitive action by bringing structure to chaos. Simple guidelines should provide the individual with a manageable framework amid all the complexity and stress of the game, helping the player to remain calm and focused on relevant information. Once he becomes more comfortable in the setting, he can gradually begin to play with increased amounts of freedom.

While we have focused mainly on the concept of anxiety, it is clear that confidence is closely related. The more confident a player feels, the less anxiety they are likely to experience. Vealey (1986) defined sports confidence as “the level of certainty athletes have about their abilities to achieve success in sport”. The strategies outlined in this article can also be effective in helping players to enhance self-confidence.

Additionally, players might consider watching personal ‘highlight reels’ before matches. If this level of technology is not available, he or she can try to remember successful moments from previous matches to remind themselves of the level of performance that they are capable of producing.

According to former Arsenal manager, Arsene Wenger, players who are low on confidence should also focus on completing simple actions during the early stages of games while they build up their self-belief, before gradually talking more risks.

To conclude, this article has examined the science behind performance anxiety, the key theories associated with anxiety intensity and interpretation, and some of the strategies that players can use to manage their anxiety. Psychology plays a crucial role in high performance, and so it is essential that players not only have the ability to control the ball, but also their minds.