Pressing & Counterpressing: Marco Rose (RB Salzburg 17/18)

Following a modest playing career, Marco Rose retired at the age of 33 to pursue coaching. A native of Leipzig, the former defender spent a year at Lokomotiv before moving to Austria to coach Red Bull Salzburg’s U16 side. He quickly progressed through the age groups and began managing the U19's in 2016, guiding them to an unexpected UEFA Youth League triumph.

His reward was promotion to the senior team, where his reputation would grow exponentially. Overcoming the likes of Borussia Dortmund, Real Sociedad, and Lazio, RB progressed to the semi-finals of the Europa League in Rose's first season at the helm. Marseille, who had finished 2nd to Salzburg in the group stages of the competition, put an end to their journey with a narrow 3-2 aggregate victory.

Rose, however, had placed himself firmly on the radar of top clubs around Europe having also secured the league title, finishing 13 points ahead of their closest rivals.

Having played under Jurgen Klopp during his time at Mainz, Rose’s philosophy bares plenty of resemblance to that of his mentor. High-intensity attacking, with a focus on verticality, are prominent features of his game model. Perhaps the most obvious similarity, Salzburg press aggressively without the ball.

Klopp once described coaching as “30% tactics and 70% team-building”, and this idea of creating a family structure within a club also appears to have influenced Rose. The 42-year-old mentioned the importance of unity in a recent interview.

“I put a lot of emphasis on teamwork and demand that from my players.”

While the creation of togetherness and trust can play a significant role in the successful implementation of such a committed style of play, this article will focus on the technical components that make Marco Rose’s pressing so effective.

Pressing Matters

Pressing is defined as applying pressure to the opponent with the intention of achieving a turnover in possession. While the idea of trying to win the ball back has existed as long as the game itself, pressing both on an individual and collective level has become increasingly coordinated and, consequentially, more efficient.

Every team tries to leave their established defensive phase at some point by winning the ball back. However, not every team can be considered proactive in their approach to defending. Sides that press do so in the hope of determining their opponent's next action, rather than simply reacting to it. Ideally, the pressure leads to a turnover in the opponent’s half. Alternatively, it may force them into playing a hopeful long pass or clearing the ball out of play.

The idea is to attack with and without possession. A proactive team is either attacking the opponents with the ball, or attacking them to recover the ball. In his book ‘Game Changers’, Fergus Connolly stated:

“In successful teams, there exists only offense. There is no such thing as defence, there is only offense without the ball.”

For the most part, Red Bull Salzburg are an attack-minded team with a pro-active approach to their defensive phases. They’ve enjoyed 61% of possession on average in the league this season, and play a quick, high-intensity game. Without the ball, there are three key phases of their pressing game. While within these phases, there are important mechanisms that make their approach so effective. This article will explore as much.

During opposition build-up

Pressing high against build-up play is often seen as a brave tactic. However, RB defender Andre Ramalho sees it as the ultimate respect for their opponents.

“There are lots of teams with so much quality and if you don’t press, it is easier for them to play. They have time to think and make the best choices. With a lot of pressure, it makes it more difficult for them to find the best solution.”

Remarkably, Red Bull only allow an average of 6.6 opponent passes before a defensive action is completed. This number ranks as one of the best in Europe, comfortably higher than the likes of Manchester City and Liverpool. Additionally, they complete 14.32 passes on average before the opposition manages to dispossess them.

When the opponents prepare to build out from the back, Salzburg typically apply a positional press in order to limit the options for progression. Although it often depends on the shape of the opposition during the first phase, the general method is to line-up in a 4-diamond-2 formation. This is deemed the best option for pressing against build-up because of it's potential to cancel out any natural numerical disadvantages. Jurgen Klopp also spoke about using a diamond whenever possible.

"I've always played a diamond when I've had the opportunity to do it, bringing in two strikers. Our system, even when we play with all three up front, is something like a diamond."

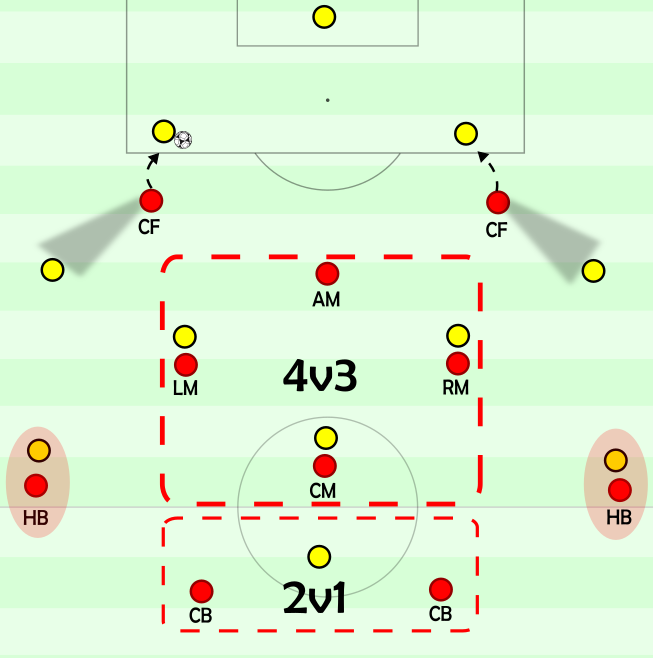

The image below provides an example of this, with the Salzburg players represented in red. The ball-near striker is tasked with pressing the central defender in possession, while shutting off the passing option to the fullback with a cover shadow. The ball-far striker positions himself between the left central defender and fullback, prepared to apply the same methods as his fellow striker should the ball be moved across to his side. The opposition wingers are occupied by the fullbacks, while Red Bull's central defenders have a 2v1 advantage over the lone striker. In the middle of the park, a 4v3 is achieved with the midfield diamond outnumbering the opponent's double pivot and 10.

This type of layout tends to force the ball back to the goalkeeper before he resigns to playing it long, where RB are well positioned to recover the first and second balls before restarting their attacking phase. The video below illustrates this. With little or no safe short-passing options available, the keeper has no choice but to play it long. The Salzburg defenders and holding midfielder consistently perform well at winning the aerial battles, with ring-fencing players well prepared to recover the knock-downs. Their high level of presence in central areas also aids the recovery of 2nd and 3rd balls.

Teams often take advantage of opponents who press by exploiting the space behind the midfield pressure. It's often difficult for the back line to retain vertical compactness when the pressure from the midfield and forward lines in front of them is aggressive. This can sometimes lead to a gap opening up between the lines, and if the team in possession are adept at bypassing the first two lines of pressure, the possibility exists to exploit this space.

However, Salzburg's diamond midfield layout aids in preventing this from occurring. It effectively provides five lines, making it easier to retain vertical compactness. Furthermore, the space that would normally exist between the lines is occupied by the holding midfielder.

Instead of marking individuals during an opponent's build-up, the Red Bull forwards tend to mark the spaces between players in order to retain access to two options at once. If the keeper takes the risk of playing out, the attacker closest to the receiving defender presses the ball while shutting off the passing option to his second man with the use of a cover shadow. It's a risk that doesn't represent great potential for the opponents, and so they usually don't take it.

While they mostly aim to force the opponents long on goalkicks, Salzburg occasionally allow them to progress out of the first phase while guiding them into a trap. Again, they shut off the centre, angling their pressure so as to facilitate passes towards the flanks before squeezing the space around the receiver and forcing a turnover.

In their away victory over Dortmund last season, Rose chose to line up in a flat 4-4-2 out of possession, electing to take a slightly more cautious approach against such a high level of opposition. They didn't simply sit back and defend, though. Instead, they allowed the centre-backs to receive from the goalkeeper before guiding their play onto the flanks. Once the fullback received possession, he would be pressed into a mistake or a clearance.

The example below illustrates this. Dortmund centre-back Omer Toprak is allowed to receive, while Salzburg's right striker, Hwang Hee-Chan angles his approach to shut off passes into pivot player Julian Weigl. He does, however, leave the passing lane open to Mahmoud Dahoud, who has pressure arriving from behind in the form of Amadou Haidara. Further progression through the centre is prevented by the angle of Haidara's pressure as he attempts to complete a turnover.

The ball makes it way out to the fullback, Marcel Schmelzer, who is pressed aggressively by Salzburg right-back Stefan Lainer. This pressure leads to a sloppy pass back towards Dahoud, with Xaver Schlager on hand to recover possession, passing it on to Haidara to dribble towards Dortmund's back-line. Lainer continues his run on the flank, where he can receive in the open space behind Schmelzer. His cross finds the arriving Valon Berisha just inside the box.

The next example comes from RB's 0-4 victory at Hartberg in November. Having backed their hosts into a corner during build-up play, the fullback is forced into a pass back to the goalkeeper. As the ball travels, striker Moanes Dabour leaves his man to apply pressure to the keeper, while also shutting off the passing lane to his initial marker. This is another key aspect of their pressing during build-up play, with opposition goalkeepers regularly pressured into panicked long passes by the striker's angled approach.

On this occasion, the keeper plays the ball into midfield. The receiver is pressed immediately by three Salzburg players, who collapse on the surrounding space to force a turnover. As with the previous example, RB's first thought upon recovering possession is to feed the open spaces down the sides, behind the advanced left-back.

Quite often, their opponents won't even attempt to build out from the back, knowing the risks attached against such a well coordinated pressing side. Instead, they empty the space in their own half before playing it long in the hope of establishing an attack off the back of a knock-down.

As we've seen, however, Salzburg are excellent at winning the aerial duels before recovering the second balls and restarting the attack. In these instances, the space exists to exploit in behind, with the opponents having pushing up towards the half-way line. Using rapid vertical combinations, they look to progress into the open space in the opposition's half.

The video below shows this. After the opponent's elect to push up and play the ball long, centre-back Marin Pongracic wins the first header. Moanes Dabour recovers the knock-down before immediately playing into the space behind Austria Wien's defence. Young striker Patson Daka provides an excellent finish. It's a goal illustrating that, regardless of the methods the opponents choose in building attacks, Salzburg are well versed to exploit them.

Overall, Salzburg are well organised and proactive in their attempt to stifle opponent build-up play, forcing them long or into mistakes on a consistent basis. Below is a summation of the core mechanisms that make RB so effective in this phase of pressing.

Opponent-Specific 'Positional Press' to cancel out numerical disadvantages high up-field, with individuals often retaining access to two options.

Press ball-occupant while shutting off passing options with angle of approach.

Creation of 'False Passing Options' to trick opponents into passing to seemingly open players, before closing out the space surrounding the receiver and forcing a turnover.

Appropriate positioning in deep areas to win first & second balls following opponent's long passes.

Exiting the 'rest phase'

‘Attacking’ for the entire game, either with or without the ball, would be unsustainable and so ‘rest phases’ allow for the recuperation of energy. Rest phases occur both in and out of possession. In possession, energy can be saved by keeping the ball in a controlled manner while expending little resource. Out of possession, the team can retreat to a deeper defensive unit while guiding the opponent's attack into specific zones.

With Salzburg pressing goalkicks and deep build-ups in general, their opponents are consistently forced to go long. Furthermore, their counterpressing following a loss of possession regularly leads to misplaced clearances. While more often than not these instances result in RB regaining possession, it isn’t always the case. Sometimes, the hopeful long ball finds it’s man. Sometimes the opposition are well prepared to bypass the pressure. On these rare occasions where the pressure applied doesn't achieve it's objective, Rose’s men are forced to retreat into a deeper organised defensive shape. With that said, they rarely drop back into a low-block, and continue to apply measured pressure in the right moments.

During their rest phases, they usually defend in a 4-3-1-2 or 4-3-2-1, closing off the centre while guiding the opponent's defenders into playing down the sides. When the play does progress via the wings, Salzburg look to trap the opponents using diagonal pressing.

Diagonal pressure is also often applied for opponent throw-ins, where Red Bull have time to organise the ideal layout. The image below provides an example of this set-up. The first line of pressure is made up of the near-sided striker, attacking midfielder, and near-sided central midfielder, with additional support coming from the near-sided fullback. Behind them, the far-sided striker, far-sided central midfielder, and holding midfielder provide cover. On this occasion, the ball is recovered by Hannes Wolf with the space closed in on and the passing options limited. The diagonal press also makes it difficult for the opposition to 're-point' the attack by playing back to the keeper, due to the positioning of the ball-near striker.

As mentioned, RB actively look to guide the opposition's first line of attack down the sides, both with their positional play and through individual body orientation. They deem progressions via the wings as less threatening. Furthermore, they appreciate that recovering the ball is easier on the flanks because the opponents only need to be pressed from one side, sandwiching them against the touchline in the process.

In the video below, we see an example of how Salzburg look to close off the central space when 'resting'. Napoli are forced to shift the play down the sides due to the level of compactness in the middle. Forward Takumi Minamino further guides the play towards the flanks with his positioning and angled approach. Once the ball progresses via the wing, Red Bull press against the touchline to close out the space and force a throw-in. As the opponents prepare to take the throw, Salzburg can organise their diagonal pressure to force a turnover of possession.

Pressing triggers also play a significant role in exiting the rest phase. These involve applying pressure upon a cue from the opposition. Examples include; a loose touch, receiving with their back to play, a backwards pass, hesitating on the ball, close proximity to the ball occupant, and a loose sideways pass. Salzburg can regularly be seen pressing on each of these triggers.

The GIF below highlights an occasion where Salzburg applied hard pressure upon receiving one of these cues from the opponent's play. The press is initiated by a sloppy sideways pass across the midfield line after Wolf had previously had access to the ball but failed to complete the turnover. The Brugge player's loose pass gives Schlager the opportunity to press, before the ball falls for Fredrik Gulbrandsen to shoot on goal.

Even when Salzburg are in their rest phase without the ball, they are active in trying to engineer turnovers. In truth, this is a minor phase of their out of possession game due to how effective they are when pressing high, counterpressing, and recovering the second ball, as well as being adept at retaining possession. The list below provides a summary of the mechanisms they use to exit the rest phase.

Retreat to out of possession 'Rest-Phase' when high press or counterpress fails, or to recover energy following high-intensity spells of pressing. Level of retreat should be in accordance with location of opponent's possession.</em></li>

Close off central progression options while guiding opponents down the sides.

Diagonal pressure to close out space against the touchline, pressing on access to force a turnover.

'Hard Pressing' on Triggers to recover possession, with the opponent's play acting as a cue: loose touch/pass, receiving with back to play, backwards pass, hesitant play, proximity to ball occupant.

Attacker can also decide to initiate pressure against the opposition's first line once sufficient energy has been recovered, with his teammates following suit.

Counterpressing

Counterpressing involves pressing the opponent in the immediate aftermath of a possession loss. Instead of transitioning into a defensive phase right away, the team who has lost possession attempt to ‘counter the opponent’s counterattack’.

The reasons for implementing a counterpressing style of transitional defending are three-fold:

Prevent the counterattack

Recover possession

Exploit opponent’s disorganisation as they transition from defence to attack

Counterpressing can be split into four main categories. Before discussing Salzburg’s preferred approach, it’s worth defining each method briefly.

Man-orientated: each player sticks to an opponent, with the player closest to the ball tasked with applying hard pressure.

Space-orientated: the players surrounding the ball-occupant suffocate the space, blocking off exit routes.

Passing-lane orientated: players shut off passing lanes in the hope of forcing a misplaced pass, or sufficient hesitation for the player closest to him to be able to make a tackle.

Ball-orientated: applying pressure to the ball in large numbers, with little thought of surrounding passing options or the retention of an organised shape.

Marco Rose and his team generally fall under the umbrella of space-orientated counterpressing, collapsing in on the space around the ball-occupant in an attempt force a quick turnover. However, they have also been seen applying other variations. During the 17/18 season, seven of their goals came directly as a result of counterpressing in the final third.

In a counterpressing situation, the opponents have switched their mindset from defence to attack, and are therefore likely to have begun the process of broadening their positional layout. This in turn creates spaces that weren’t previously there. If the ball is recovered during these moments, the opportunity exists to exploit the new space before the opponents have a chance to transition back to an organised and compact defensive shape.

In order for counterpressing to be effective, It is necessary to create the right conditions ahead of time. If the attacking shape is too broad or disjointed, the immediate instance following a loss of possession will be equally so. In order to be effective in each phase of the game, the relationships between those phases must be close.

As we’ve seen, Marco Rose’s teams typically attack in a 4-diamond-2 formation. The fullbacks arrive to provide width in the final third, but overall the shape can be regarded as being quite narrow, and therefore has a high level of horizontal compactness. This level of compactness in central areas serves to aid their vertical focused attack, but is equally beneficial to the defensive transitions. With large numbers around the ball in tight central spaces, an opponent who dispossesses them can be pressed easily from all angles. The video below highlights this effect.

Following a misplaced pass in the final third, three Salzburg players immediately seek to close out the space surrounding the ball-occupant. His passing options are shut-off and he has nowhere to go in a 1v3 scenario. The inevitable occurs as RB recover the ball after less than two seconds before feeding the open space on the outside. Notice also the influence of the pressing players coming from behind the player in possession when recovering the ball, this is known as a 'blind-side dispossession', and is another common feature of their counterpressing game.

As shown by the video, there are a number of key mechanisms that determine the success of a counter-pressing situation in relation to making the initial ball-recovery. Namely: numbers in central areas to close out the space around the ball-occupant, angled pressure to shut-off passing options and a high level of intensity to ensure the opponent can't exit the pressure.

What happens next is also key. As mentioned, the opponent's switch from an established defensive state to an attacking transition state, meaning the wide midfielders often leave their supporting defensive roles to charge forwards. Sometimes the fullbacks will even push on. This natural tendency to broaden the play in the attacking phase often leads to new spaces opening up.

Whenever Salzburg counterpress successfully and recover possession during the opposition's attacking transition, their next thought is to exploit the 'new space'. The video below highlights this, with an example of Red Bull winning the ball back high up the pitch before exploiting the space down the sides and completing a cross to the box.

Many pressing teams will have a general rule regarding how many seconds should be spent counterpressing before retreating to an established defensive phase should the press fail. However, having ‘access’ to the ball occupant can influence this number. Salzburg tend to counterpress for less than five seconds. However, If after this time they still have good access to the ball and the opportunity remains to recover possession in the transition, they can extend the counterpress further. Once the five seconds are up or access has been lost, they retreat to their established defensive shape/rest phase.

Another interesting aspect of their game, Salzburg also apply their counterpressing principles to exploit the 2nd phase of attacking set-pieces. If their initial delivery is cleared, they are well placed outside the box to recover the ball before attacking down the sides. The normal action for the opposition in these moments is to push up and out.

In this second phase of defending, the likelihood is that of decreased opponent organisation. Spaces open up around the sides and in behind, and if the ball can be recovered by the attacking team, the opportunity exists to exploit this disorganisation. The video below highlights this effect, with RB creating two goals and an additional clear-cut chance all from the 2nd phases of set-pieces in the same game. Notice the defenders' positioning as the final crosses are played. In an organised 1st phase, the defenders would likely be goal-side of their markers and with a better body orientation.

During his 2016 appearance on Monday Night Football, Jurgen Klopp called counterpressing situations 'the best playmaker in the world', and when you watch RB Salzburg play, It's hard to argue with this sentiment. Below is a recap of the key components that make their counterpressing so effective.

Numbers in central areas during attacking phase in order to create the appropriate conditions for the counterpress.

Pre-set duration of counterpress, but allow added seconds on occasions where quality access to the ball in advanced areas exists for longer than the pre-set time.

Space-orientated pressure. Close out the space surrounding the ball-occupant in numbers and with a high level of intensity.

Shut off exit routes and passing options to force recovery.

Players on the outside positioned well to press should the opponent exit the initial pressure.

When recovery of possession succeeds, feed the 'new space' down the sides before crossing to the numbers arriving in the box.

Exploit opponent disorganisation during the 2nd phase of set-pieces with the same principles.

Conclusion

When it comes to pressing, Marco Rose is one of the most noteworthy coaches in the modern game. His teams are well coordinated in each pressing phase, and the instructions given on an individual level have made Red Bull an extremely effective team out of possession.

Rose is a progressive young manager, and a move to Borussia Monchengladbach has already been confirmed ahead of next season. Fans of the Bundesliga club are sure to warm quickly to his positive, intense style of play.

After a thorny playing career, Germany's Rose is beginning to bloom.