Generating Forward Passing Lanes

In order to achieve the objective of progressing the ball into the spaces close to the opponent's goal, a central element of any game model must involve the consistent creation of forward passing lanes. As we will see, an attacking team's basic build-up structure can help to maximise the number of quality options ahead of the ball. However, the opposing team's defensive system will force dynamic movements and innovative strategies in order to create or maintain the desired 'lines of pass'. It is also true that an attack can still be progressed in the absence of any forward passing lanes. A dribble on it's own can be used to advance the play when no quality passing options exist ahead of the ball, while a lofted pass can help to gain access to a teammate behind opposition lines. This article, however, will focus on the variety of ways in which a team can generate forward passing lanes on the ground.

Positional Structures & Dynamic Adjustments

Every formation comes with strengths and weaknesses. Meanwhile, the dynamic nature of football means that positional structures can only provide us with a 'base' shape to work from in each phase of the game. We will discuss the importance of adapting to the opponent's defensive shape soon, but it remains worth considering some of the most popular build-up structures and how they naturally influence the options ahead of the ball in different ways.

For advocates of Guardiola's 'positional play' model of attacking football, importance is placed on having no more than two players on a vertical line. The consequence of this principle is that players will rarely find themselves in situations whereby one of their own teammates is blocking off a vertical pass to another teammate further forward. This allows them to consistently maintain options into 'depth', facilitating progression into the attacking third of the pitch.

Of course, diagonal passes also represent a valuable opportunity to progress play as they shift possession both vertically and horizontally, significantly disrupting the opponent's defensive organisation in the process. A 4-3-3 in the offensive phase may naturally lead to a maximum of three players on some diagonal lines. This will inevitably mean that on occasion, players will be positioned behind their teammates when a diagonal pass is being lined up. 4-2-3-1 & 3-4-3 are two other popular modern-day formations, and also typically result in no more than two players on a vertical line and no more than three players on a diagonal line. Meanwhile, a 4-diamond-2 line-up can sometimes result in up to three players on the same vertical line and up to four players on the same diagonal line.

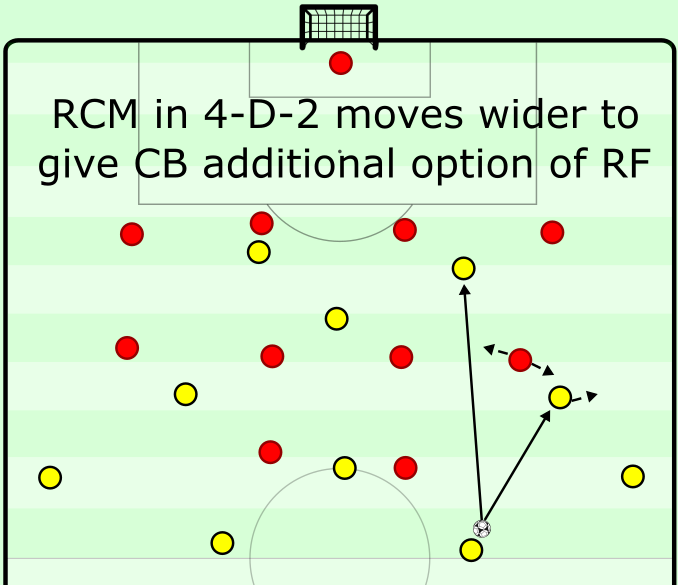

Although this might seem like an argument against playing 4-diamond-2, or a suggestion that formations like 4-3-3 are more effective in generating forward passing options, this isn't the case. Just because a player is blocked off from receiving certain passes by his own teammate in the side's base shape, doesn't automatically mean that it's a problematic structure. As mentioned, positioning should be dynamic and players should adjust to fit the demands of the situation at hand. To put this into context, imagine the right centre-back in a 4-D-2 is in possession. If the players ahead of him maintain their base positions, The outside right midfielder in the diamond may be blocking off a longer pass to the right striker. In order to correct this, the outside right midfielder can simply move slightly further towards the wing, giving the right centre-back two potential passing options instead of one. In this scenario, illustrated below, who emerges as the free player to progress the attack will depend on the decision of the opposing left midfielder.

"Johan Cruyff would expect that our positioning would be related to our teammates. Why? So that we always had the option to pass the ball at any moment, to keep the game going."

Ideally, a structure would exist whereby no players were positioned directly behind their teammates on vertical or diagonal lines. However, it is far more important that the team has continuity in their basic structure. In order to achieve this, emphasis should be placed on maintaining options into depth and staggering of positions to create the potential for passing chains and connections up the field. Additionally, the opponents' defensive scheme is likely to continually force the attacking players to adjust their positioning to remove themselves from cover shadows or close marking. Overall, a formation is just a starting point and positional play must constantly be altered to ensure that the ball-occupant retains some quality options to progress the attack.

By the same token, the player on the ball can also adjust his positioning to find a line of pass by making use of a dribble. If limited forward passing options exist, a player confident in his close control might choose to shift the ball into a different location in order to combat opponent cover shadows and access an open passing lane. The dribble action is also likely to provoke opposing players into applying more pressure, thereby disrupting their defensive positioning and creating more space for the eventual receiver. The two examples below highlight this concept, with Dayot Upamecano and Kyle Walker using their dribbling ability to carry the ball into a position where improved access to the forward players exists.

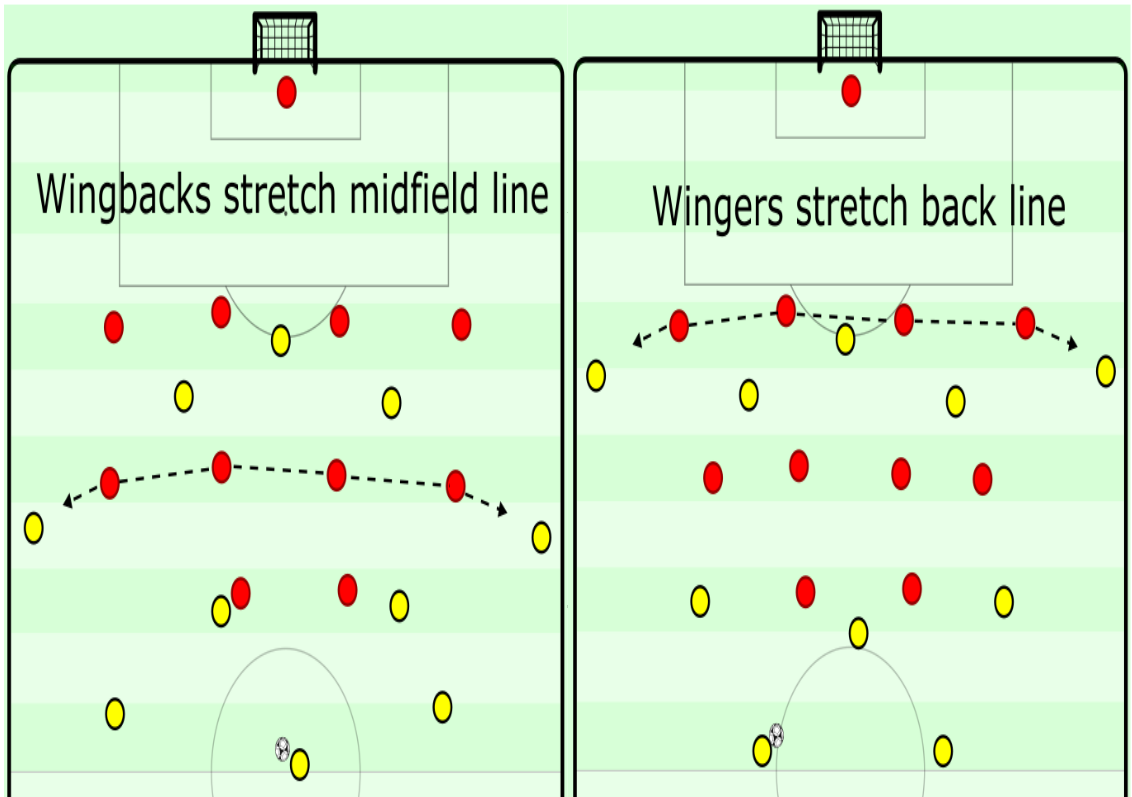

Another important consideration to make when designing build-up structures involves the principle of width. Along with giving the team the option of playing around the opposition as well as through, players positioned out wide can force the opponents to stretch their defensive lines horizontally, increasing the distances between one another and consequentially leaving gaps for the attacking team to progress centrally. Fullbacks positioned in line with the opponent's midfield can open lanes for the in-possession deep midfielders or centre-backs to penetrate through the middle and feed the attacking players in the space in front of the opposition's back line. The forward line can also provide width if the wingers starting positions are close to the touchline. The opponent's backline may be stretched in order to retain access to these wide attackers, creating gaps to penetrate in behind.

Overall, the basic layout a coach chooses to set their team up in will have some influence on the number of forward passing options that exist, both vertically and diagonally, in a given situation. However, as we have discussed, the players ahead of the ball and the ball-occupant himself must be dynamic by adjusting their location on the field according to the circumstances. Constant referencing of the ball, teammates, opponents and space is essential for the attacking team to maintain quality passing options, all the while ensuring that an overall desirable structure that incorporates depth, width and staggering is not sacrificed.

Links & Chains

As mentioned, it is important to maintain staggered positioning in order to facilitate chain progressions up the field, especially where space is congested and one-touch passing sequences are required. Simple link passes via the wide players can also help to gain access to central players behind opposing lines, while a lay-off from a forward can allow a third player to take possession behind a cover shadow and facing forward. In this section, we will examine how each of these strategies can be best utilised.

Before assessing these tools, however, it is important to quickly discuss one of the basic elements of the '3rd man' concept. When looking to advance play, the player on the ball will look forward to see which of his teammates has created enough separation from nearby defending players and therefore found space to receive possession. Should an open passing lane exist between the ball-occupant and the player in space, progression can take place seamlessly. But as is clear throughout this piece, the opponents' defensive movements and positioning will often eradicate these lanes, making the task of advancing play more complicated.

The player on the ball might choose to accept that despite the fact his teammate has found space to receive in forward areas, he is inaccessible due to the opposition's cover shadow. Alternatively, he could think one step ahead by understanding that If he isn't in a position to access the free player ahead of the ball, he should pass to another teammate who is. One simple example of these 3rd player sequences involves deep-lying players using a wide option as a link in order to access a free player between the lines. If central passing lanes are cut off, the likelihood is that the opponent's midfield line is narrow and therefore, space should exist for someone to link the play from a wide position. If the widest opponent on the midfield line does manage to get out and press the link player, more gaps should now exist centrally. The image below illustrates how link passes can be used to access the free player in space.

Lay off passes also provide the opportunity to access players behind cover shadows. Furthermore, the player making the lay-off isn't required to be completely free because his role is simply to play a first time back pass to the 3rd man in the sequence. There are numerous other benefits to lay-offs and full 'up-back-throughs'. For example, the first receivers dropping movement and the fact that he is taking the ball facing his own goal should act as a pressing trigger and as a result, is likely to draw a defender out of position, giving the 3rd man gaps to play through the opponent's back line. Additionally, the 3rd man can receive possession facing the opposition's goal, allowing him to play forward immediately without the need to turn. The examples below illustrate this concept.

When defensive opponents are well drilled in congesting central spaces, forcing the attacking team down the sides before also crowding those areas, progression can become extremely challenging. But as we saw with the lay-off passes previously, creating conditions whereby continuation of the play can occur using one and two touch actions can overcome the limited amount of space and time available. As described by former Barcelona player Carles Rexach below, when the team in possession executes quick combinations effectively, it can make it nearby impossible for the opponents to dispossess them.

“If you pass, the player marking you doesn’t have time to catch you. When he gets to you, it’s too late. That’s how you take control."

Of course, the best teams in the world make one and two touch passing sequences look simple, when in reality they require a high level of technical control to carry out. However, any team can create staggered structures that give them the possibility of progressing through congested areas quickly. 'Zig-Zagged' positional play, either down the sides or through the middle, allows players to gain access to forward areas that appear closed off by the opposing team's defensive unit. Much like the strategies discussed previously in this section, they involve thinking about the continuation of the play beyond the first pass. Each player is positionally prepared to receive and pass immediately to the next player in the sequence, giving the opposition no time to adjust and prevent progression. The clips below highlight this concept in action.

As shown, a variety of conditions can be created to give the ball-occupant indirect access to teammates behind opposing lines. Basic links via the wide players can overcome midfield covers to find a free player in space, lay-offs allow third receivers to take the ball facing forward and behind defensive lines, while staggered positional structures can facilitate one and two touch progressions through congested areas.

The Accordion Effect

Quite often when playing against a deep-lying defensive unit, almost all of the opposition's players will be positioned on the ball-near half of the field, resulting in an extremely narrow block with limited spaces for the attacking team to play through. Of course, such a level of compaction on one side of the pitch means that vast space exists on the other side, meaning that the use of quick switches can free up a player on the far side to exploit the open zone.

However, when the opponents manage to retain sufficient access to both sides, these switches of play can become far more difficult to execute. This is frequently the case when playing against back fives because the longer horizontal line of defence can shift more easily to restrict the option of a direct diagonal pass to the ball-far wide player. In scenarios like this, where quick switches aren't an option, it's important to make use of horizontal circulation of possession, capitalising on what is often referred to as the 'accordion effect'.

The accordion effect occurs when fluctuations in the motion of a travelling body causes disruptions in the flow of elements following it. In footballing terms, this relates to the spaces that emerge when a defensive unit moves from side to side. Along with the fact that the opponents can't move at the same pace that the ball can, some of the defending players are also likely to move at slightly greater speeds to some of their teammates on the same line. Furthermore, one player may make the decision to change the direction in which they shift their position slightly before one of the other players does. These differences in speed lead to increased distances between the defenders, therefore giving the attacking team the opportunity to penetrate centrally.

As mentioned, this effect can be achieved with horizontal passes from one flank to the other. Speed of passing and quick changes in the direction of possession are crucial components in these circumstances to maximise the prospects of gaps appearing. It's important to avoid sterile circulation of the ball, as this would give the opponents the ability to shift in a controlled manner and to maintain the desired level of spacing between one another. The examples below provide evidence of the accordion effect in football.

Many pundits and fans will criticise sideways passing. However, just like vertical, diagonal, and backwards passes, there are unique benefits that exist when horizontal passes are carried out with intent. Of course, moving the ball from side to side in search of openings also requires players behind opposing lines constantly adjusting their positioning to get into the line of pass for the ball-occupant, allowing them to exploit any gaps that emerge.

Decoy Actions

Given the relentless pace at which top level football is played nowadays, players often try to second guess their opponents. Much like a goalkeeper attempting to save a penalty, defenders regularly try to predict what their opponent’s next move will be in order to provide a reaction before it’s too late. In this sense, defending players react not only to actions, but also to implied actions. Theoretically, this allows them to be better prepared to deal with the subsequent action. In practice, however, a player’s actions don’t always match up with their prior implication. This conflict between what the defender thinks the attacker is about to do, and what they actually proceed to do, can be significantly advantageous to the attacking player.

Using 'false implications' to draw a response from an opponent before taking advantage of their disposition is a common strategy in a wide range of sports. In the moment between an implication and an action, the attacking player potentially has a distinct advantage. If they match their action with their prior implication, they hand the advantage to the defender, who has likely prepared himself to deal with such an outcome. However, if they mismatch their action and implication, they take advantage of the fact that the defender has conceded space and time in reacting early. By leaving their position and preparing for what they perceive is about to happen, they create a gap that didn’t exist initially. Furthermore, they give themselves no time to react again to a converse action.

False implications can therefore help attacking players to eradicate an opponent's cover shadow, opening up a forward passing lane as a result. Barcelona's Sergio Busquets is the master of disguised passing, regularly using misleading body orientation and eye direction to imply that he intends to feed the wide player in space, urging opposing players to move towards the wing in anticipation. Finally, he uses a converse action by reversing his pass into a central teammate instead, exploiting the newly opened lane. Once again, this concept relates closely to that of the third-man. Generally speaking, the attention of defending players will be focused primarily on the player in possession of the ball, and the player who appears most likely to receive possession next. Quickly adding a third player to the sequence can make it difficult for the defending team to re-adjust accordingly. The first clip below provides an example of Busquets executing the reverse pass strategy, while the second example comes from Norwich playmaker Emiliano Buendia.

While the above actions involve the ball-occupant making use of decoys, misleading off-the-ball movements can also be of great benefit when it comes to opening forward passing lanes. The idea of using decoy movements to create extra space for teammates in the final third is well-known. However, more and more teams are engaging in misleading movements deeper in build-up play with the intention of opening passing lanes for their teammates to penetrate. When his centre-backs are being marked closely, German coach Tim Walter will often task them with dragging their markers into positions that intentionally create previously closed-off lanes for the goalkeeper to pass through. Meanwhile, midfielders under coaches like Thomas Tuchel and Pep Guardiola will regularly take advantage of close marking by drawing opposing players away from the centre, increasing the gaps for the centre-backs to pass directly through to the attackers.

Although decoys might seem like a somewhat passive strategy, given the reliance on the opponent's response for them to be fully effective, the fact is that they are likely to create one of two positive conditions. Ultimately, a decoy movement in any form presents opposition players with a dilemma: Do I follow my man, leaving space or open passing lanes for his teammates to potentially exploit? Or do I hold my position and allow him to receive unmarked? Neither option is attractive, and this cognitive discomfort in itself can lead to poor decisions from the defender. More often than not, especially in heavily man-orientated schemes, the defending player will follow his man. The examples below highlight this effect.

As we have seen, decoys movements can give marked players the opportunity to positively influence the play without having to get free from their marker or touch the ball. Meanwhile, misleading body orientation and eye direction from the ball-occupant can exploit defenders' tendency to anticipate an attackers next act, shifting their position in the process and thereby opening up previously closed off spaces.

Conclusion

Throughout this piece, a variety of concepts that facilitate forward passing have been discussed. Positional structures can help to generate the necessary conditions to progress up the field, but as we know, the opposition's defensive schemes will force dynamic adjustments if sufficient lines of pass are to be maintained. Links and chain passing sequences allow the ball-occupant to plan ahead and access free players indirectly, while misleading implications can shift defenders and open up previously closed-off passing lanes. Finally, quick horizontal circulation of possession can cause the distances between opposing players to increase, therefore creating opportunities to penetrate centrally.

KlipDraw discount: http://bit.ly/8k3HvzoWXU